7 Lessons from Jim Collins on The Tim Ferriss Show

“I’m not really a business author; I just happen to have used companies as the method to study human systems because there’s great data.”

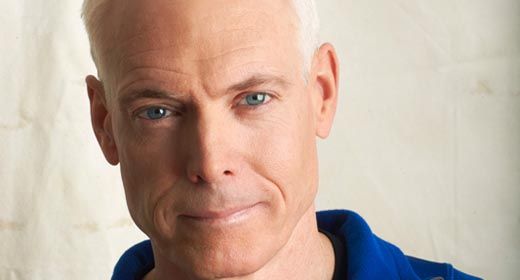

Jim Collins

Jim Collins is an author, teacher and consultant focused on business management and what makes for successful, sustainable company growth.

With over 40 years experience and a number of

I’d recommend diving into the full episode as there’s lots of good stuff in there, but for an express view here are some of the insights from this episode that I found especially interesting.

Attention Seeking

Most of us are seeking something – recognition, community, respect, attention.

We want to be visible.

Collins went the other way, from being visible to the relative invisibility of the deep, quiet solitude of work.

Instead of the default setting of our focus being on visibility, aim it towards being invisible. Place little attention on receiving attention from

His rule of 50/30/20 also starts to come out here – 50% working on new, innovative, creative work, 30% teaching, and 20% on whatever else you have to do.

Creative Hours

The 50/30/20 rule rapidly shifted towards a higher proportion on the 50% – the creative, innovative work.

The problem with this is not every day can yield 50%+ creative work – there’s just other stuff that needs to happen or gets in the way.

Instead, expand this outwards to a rolling 365 day approach.

Every 365 day cycle, whether Jan 1-Jan 1, Oct 31 to Oct 31, the amount of creative hours must exceed 1000. Every year.

And ‘creative hours’? Collins defines it any activity has a link to the creation of something new, and is potentially replicable or durable.

It’s worth noting this may be painting the canvas, preparing the brushes, or even ordering the paint – anything that’s in direct service of that work. The important thing is that the work is going towards the creation of something new.

Jump to around 47 minutes for the full the description of how this works (plus a broader day-grading method which is well worth trying out), but the overarching point is to shoot for 1000 creative hours each year.

Hedgehog ahead of Career

Collins doesn’t think about traditional careers.

There are 2 forms the hedgehog can take – one for companies, one for individuals.

The hedgehog model is made up of 3 intersecting circles, made up of the following.

Companies

What are we passionate about? If we’re not passionate, we won’t be able to ensure long enough to do something exceptional

What can we be the best in the world at? You don’t need to be a big firm to do this. It’s very possible to be a small local restaurant in a quiet town and be the best in the world at the specific thing you’re doing. In this case, what’s something that a big company moving into town just couldn’t replicate? This asks us to think more laterally – about service, style, understanding our customers, combining our skills and expertise.

What’s the economic engine we can build? To keep doing this work

Individual

What am I passionate about? What’s the thing that makes you want a long life because you love doing it?

What am I encoded for? Not what you’re the best in the world at. We don’t only want one fireman or orthopedic surgeon after all. Instead, what are you genetically encoded for? Note that this is more than just what you’re good at. This can be hard to find, so use Collins’ bug method to help (see below).

What’s the economic engine I can build? As above – how does the engine work and how do you keep it running?

If you’re familiar with the Ikigai model then the Hedgehog may sound familiar. For me, the difference is the focus towards building a flywheel (which is the topic of Collins’ new book – also listen to the full episode for more on this)

The individual Hedgehog model can be particularly useful for people in their 20s. It’s tough to know which direction to focus our time and energy on during these times: picking a regular career doesn’t usually align us too well, especially if we want to take a creative path. The H

For more on the Hedgehog concept, listen to the segment around 1hr 20 on studying oneself like a bug.

As a side note, I’m interested to explore what this means for individuals who are also companies – the freelancers, companies of one, portfolio careerists and so on.

Preparation and reflection for meetings

As part of a segment discussing one of his mentors, the leading management thinker Peter Drucker, Collins mentions the value of preparation for meetings.

You’re doing a disservice to both yourself and the person you’re meeting if you fail to prepare.

Arguably even more important is to write up everything after the meeting. That’s where the real learning happens.

As proof, at the very end of the interview, Collins says the main reason he decided to say yes to appearing on the podcast (he is well known for saying no to the vast majority of things) was Ferriss’ reputation for preparing – his prepared curiosity.

Longevity

Also in the Drucker segment, Collins talks about a bookshelf that held all of the first editions of Drucker’s 30+ books.

He looked for the point of retirement age – 65 – and where that point was on the bookshelf.

It was one third of the way along. Two thirds of Drucker’s work was written after the age of 65.

As for which of the books he was most proud of?

‘The next one!’

I’m writing this as Frank Gehry is about to turn 90. Similarly, his arguably greatest works came about after his retirement age.

We know live is short. But don’t underestimate how long we can keep going.

Calibration and cannonballs

Think about you or your company like a boat in the ocean, and your efforts like a supply of gunpowder.

You can shoot bullets or shoot cannonballs.

You can go ahead and fill the cannon with all the gunpowder. Hit the target, you win. Miss, you’re done.

Instead, shoot a few bullets to get empirical validation. Each bullet you shoot should give you a little more calibration on where the target is.

Once you’re calibrated and have a line of sight, start shooting the cannonballs.

A related point here is when you should be using all the gunpowder. Sometimes when you’re on a creative path you don’t want to keep anything in reserve. Being able to go back to where you were before is a crutch, and means you won’t go all-in once you’re calibrated on where you want to head.

Useful > Successful

This one is simple.

Don’t ask yourself how you can be successful.

Instead ask yourself how you can be useful.

Another way of thinking about this is perhaps best left to Collins’ mentor Peter Drucker and how he thought about his work:

‘How can society be both more productive and more humane?’

Being useful is probably a good start.